In recent times there has been a lot of talk on how big

China’s digital trade actually is and to what extent it poses a threat to the

global economy. China is big and appears successful in digital trade, and

therefore the logic goes that China is leading

the field. Others are more careful

in cheering China’s digital success. The truth, however, is that there are two

versions to the story. One is centred around the fact that China is indeed big.

The other focuses on the extent to which China is actually competitive. The two

stories are connected, yet extremely different.

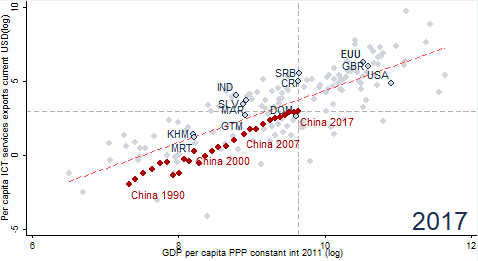

Both narratives are respectively illustrated in panels A and

B below.

Panel A shows what I call the political story. This story

reflects the fear of China becoming the biggest digital trader in the world. The

panel shows digital services exports on the vertical axis (in USD log scale to

compile the pattern) while showing the level of development (in USD PPP) on the

horizontal axis for the year 2017. I take digital services and not digital

goods for two reasons: One is that services reflect the future of digital

trade; two is that the pattern for digital services and goods is the same, so

analysing both would merely be repetitive. (There is one big difference between

digital services and goods which I will address later).

First things first though, an upward sloping line appears on

the vertical and horizontal axes in Panel A. It means that countries that

progressively become richer also become more successful digital services exporters.

How that works doesn’t matter for now. What matters is that the two indicators

are tightly connected. Countries such as the US and the UK are much more

developed and have greater levels of digital services exports; unlike Cambodia (KHM)

or Mauritius (MRT).

Panel A: China is big and will continue to grow bigger in

digital services trade…

Panel B: But China is uncompetitive and is likely to remain

so in digital services trade.

Source: Author's; WB Development Indicators.

The remarkable thing about China, is that it has been a big

digital trader throughout history, and is likely to remain so. That can be seen

by the red dots which denote China from 1990 till 2017. At any year, China was

a far bigger digital exporter than any country with a similar level of

development. For instance, in 2000 China’s level of development was equal to

Cambodia’s level of development today, i.e. in 2017. Yet China’s export in

digital services were already bigger back then, than Cambodia’s is right now.

What’s more remarkable, however, is that China has caught up

incredibly quickly with the world’s biggest digital traders. Panel A shows that

since the 1990s China has steadily approached the EU, US and UK. All three are

richer and have also historically shown a high level of digital services

exports. But China, standing at a lower level of development, has managed to

increase its export capacity in digital services, to a level in 2017 where it

reached a par with the UK. The EU and US are still bigger digital traders, but

it will only take about another 10 years before China reaches an equal footing

with these two trade giants.

That has repercussions in the political sphere, particularly

when negotiating trade deals. Bigger countries naturally have more weight in

trade negotiations. However, they do not always naturally have a bigger trade

basket, as they have bigger domestic markets which they can rely on. China’s

case is different, as it has traditionally used trade as a successful strategy

for economic development. Today the EU is still the biggest exporter of digital

services, ahead of the US and China. It therefore currently has the biggest heft

when negotiating digital services trade issues; far bigger for instance than the

UK will ever have.

In short, the political economy discourse about the “fear”

of China’s digital trade success, which one can read daily in the popular media,

stems in great part from the sheer size of the country. Don’t get me wrong,

size does matter, and it certainly makes a difference on how successfully countries

like Guatemala or China can negotiate in trade negotiations. For instance,

China has been a big trader in the past of ICT or high-technology goods. Indeed,

at all levels, it has been a bigger trader in digital goods than all other

countries, including the EU and US (Panel C). As such, China has influence on

international digital trade negotiations.

However, there is another perspective on the matter, which I

call the economic story. That story is reflected in Panel B. Economists have

always been sceptical of the idea of using plain magnitudes expressed in nominal

or absolute numbers. Rather, economists tend to transmit their messages in “normalized”

numbers, so that any form of size, quantity or volumes are instead computed as

ratios, weights or proportions. The big reason for doing so is that otherwise

numbers may be biased in favour of other characteristics, such as in our case the

huge size of a country. After all, China may be big, but that may not tell us

anything about its true economic success.

Panel B investigates how competitive China is once we

disregard its sheer size. Note that I again analyse digital services trade, as

my view is that this is where the future of trade is heading. Interestingly, using similar metrics as in Panel A, the

story gets reversed. To correct for China’s size when using its nominal numbers

of digital service exports, I divide this variable by its population.

Through

that way I obtain a more neutral representation of the true extent of China’s

export success, which economists typically call the per capita exports. It’s a

much fairer way of comparing China with other countries, as smaller countries

trade a much smaller amount. Once we divide the absolute size of digital

services exports by the number of people in each country who potentially trade,

an undistorted picture of the true strengths of digital trade exports is

presented. In other words, it shows the real digital export competitiveness.

Looking at Panel B, it becomes clear that China’s real

digital trade competitiveness is actually much lower compared to using non-normalized

trade figures. In fact, the red dots that denote China’s development over time,

are all placed below the dashed fitted values line, which represents the

“average” trend between how rich countries are at a certain level and their per

capita digital services exports. Compared to other countries, China is less

competitive in digital services exports than can reasonably be expected based

on its level of wealth.

That was true in the past and is true in the present. For

instance, back in 2000, when China shared a similar level of development as

Cambodia today, the latter exported more digital services when the size of the

market was accounted for. Similarly, in 2017, Guatemala was able to export more

digital services on a per capita basis than China did in 2007; when the two

countries shared a similar level of economic development. Today, China is as

rich as Serbia or Costa Rica, but the two latter countries are far more

competitive regarding digital services trade, given their rate of economic

development.

What’s more, there are little signs that China’s

competitiveness position is approaching any average midpoint value (dashed

line), based on what could be expected when taking into account the level of

development of all other countries in the sample. Nor does China approach the

competitiveness position of the EU, the UK or the US. (Note that the US suffers

from a relatively low level digital services export competitiveness, meaning

that for whatever reason the country is performing below its potential given

its already massive success.) In fact, the EU is in a pretty good shape as it

is placed above the fitted values line – although several other countries are

doing much better still.

So, what should the conclusion be when putting these two

panels together? Well first, one big message from this exercise is to show that

one shouldn’t conflate size with “real” size. Yes, China may be big, and the

economic size of China may disturb us from time to time, but it’s another thing

to claim that because of its size the country is going to be a giant success in

all manners of our digital life, and take over the digital world economy. Sure,

China has success in some parts, and perhaps many parts of the digital economy,

but not in all parts. In goods, the country is a major success, and so too it

seems in digital goods (compare panels C and D in the annex). However, for

digital services the story is a different one.

Second, the fact that China is precisely less competitive in

services has implications for future trade. The world economy is increasingly

shifting into an invisible one in which services, data, technology ideas and

know-how are replacing goods, commodities and other physical inputs. In this

intangible world, China appears to be far less successful compared to other big

trade giants. Moreover, China is also very restrictive

when it comes to digital trade, data and internet technologies. Different

digital standards and restrictive digital policies, such as China has today,

are harmful for its digital services trade and eventually real export

competitiveness (Ferracane

and van der Marel, 2018).

Therefore, it remains to be seen whether China’s isolated

stand regarding data and the internet will prove to be beneficial for improving

its export competitiveness the long run.

Panel C: China is big and will continue to grow to be the biggest in digital goods trade…

Panel C: China is big and will continue to grow to be the biggest in digital goods trade…

Panel D: And China is competitive and is likely to remain so in digital goods trade.

Source: Author's; WB Development Indicators.