As

traditional trade measures at the border such as tariffs have come down and as

more items in the economy have become tradable, policy reform has focused on

dismantling trade barriers that are “behind-the-border”.

These measures span a

wider variety of goods and services on which traditionally only domestic

regulators had a quasi-monopoly on to develop and advice policy. Over time, as these

behind-the-border measures inhibit trade, regulators need to strike a balance

with trade negotiators.

This is

also true for “trade in data” or the cross-border flow of data. Data has become

an item that crosses borders many times and which form an item in trade

agreements these days such as in TPP.

This is also true for the EU where the Privacy

Shield has been developed, which is a framework that provides companies on both

sides of the Atlantic a mechanism to comply with EU data protection requirement

when transferring personal data from the EU to the US in support of

transatlantic trade.

Before the European Commission could adopt the shield, the Article 29 Working Party committee or the data protection authority, which is in fact not the regulator, but a platform that provides general expert advice on data protection matters and advised the Commission by giving an opinion on the proposal. This is a good thing as certain rights need to be protected in light of an item that becomes increasingly an economic one.

Before the European Commission could adopt the shield, the Article 29 Working Party committee or the data protection authority, which is in fact not the regulator, but a platform that provides general expert advice on data protection matters and advised the Commission by giving an opinion on the proposal. This is a good thing as certain rights need to be protected in light of an item that becomes increasingly an economic one.

It’s a

classic example where policy makers need to strike a fine balance between an

economic need (commerce) and a noneconomic goal (right of privacy). The point for

this platform, which is composed of National Data Protection Authorities from each member state, the European Data Protection Supervisor and the European Commission, is to provide an opinion that would entail a removal of overly burdensome and restrictive regulations in attempt no

efficiency is lost and yet secure the concern of data subject.

However, the

issue here is the configuration of the Working Party committee itself. Since the Working Party committee will ideally need to strike this balance between commerce and societal

benefits, one would expect that their membership composition would be

distributed accordingly.

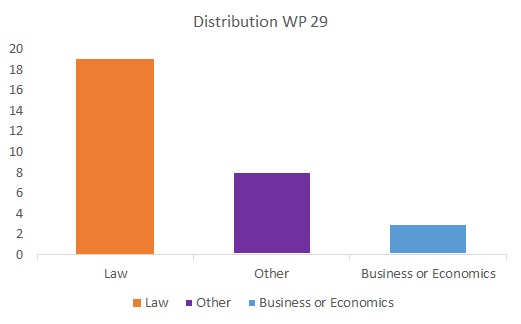

This is not the case however. Far from it as a matter

of fact. The platform has in total 30 members (excluding one member

from the European Commission). One from each member state plus a supervisor and

an assistant supervisor. By checking each member’s background, the figure below

presents the composition of the committee members by professional

background.

What

strikes me is that a large majority of its members have a noneconomic

background. The fact that most members are lawyers comes as no surprise and no

reason for worry as the platform advises on European Community law. However, there are only two members with an economic

background and a third one with a business background. Other educated professions

that were included ranges from policeman to journalist.

In age where the issue

of data becomes an essential ingredient for economic activity, data subjects

need protection. Yet, reaching the fine line between economic and noneconomic concerns

starts in my view with a balanced composition of expertise and skills of those

who provide expert advice upon policy.

No comments:

Post a Comment